All about interviews of my favorite celebrities and other articles.....

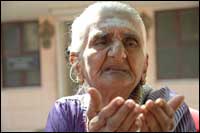

Burdened with so many preconceived notions about the elderly, I didn't expect a 106-year old lady to walk briskly towards me, speak in a strong voice (that too in five languages), hear very clearly and remember things that happened a century ago. How wrong and foolish I felt after meeting Saraswathy Ramaswamy, freedom fighter and Gandhian.

As I waited for her in the lobby of Vishranthi, an old age home for women, she came rushing towards me with folded hands. Holding my hands close to her cheeks, she said in English, "Thank you for coming, Sir (she calls everyone Sir). I look forward to speaking with you."

Then, sitting in the front yard, under the shade of all kinds of trees, she began to rewind the clock.

January 1, 1900 A little girl was born to a young couple in Secunderabad. Distraught on seeing a female first born, the young man's sister ordered the baby to be thrown into the Hussain Sagar. She was promptly wrapped in a silk cloth and thrown into the water.

A little girl was born to a young couple in Secunderabad. Distraught on seeing a female first born, the young man's sister ordered the baby to be thrown into the Hussain Sagar. She was promptly wrapped in a silk cloth and thrown into the water.

Fate had other plans for the baby though.

The midwife who delivered her happened to see the bundle floating in the river while she was washing clothes. Horrified, she took the baby back to the young mother, who was sobbing uncontrollably.

The child was named Saraswathy, and the astrologer who read her horoscope said she would live long and become famous!

"God didn't want me to die that easily," Saraswathy Amma laughed loudly. "Death came close several times, but I survived. A couple of years ago, a tree fell on my house and me. But here I am!"

At the age of 7, two major events occurred in her life. She began going to school, and she was married to a 12-year-old boy named Ramaswamy. She stayed with her parents until she completed her Bachelors degree though, travelling across India. "I was sent to my husband's house when I attained puberty at 18. It was the custom."

Joining her husband was an unexpected turning point in her life. The young Ramaswamy was so drawn to Mahatma Gandhi's call for freedom that he chucked his job as an assistant postmaster and decided to devote his life to his country.

"I was not sad when my husband left the job and gave his property to the Congress. I was proud to be part of a big struggle. If not for him, I would have remained in one place and, like all women, would have thought of my own family alone. But my husband made me believe my country is bigger than everything else in life."

When Gandhi came with his wife Kasturba to Nagpur, where Saraswathy then lived, she went with her friends to meet them. "I asked Kasturba what I could do for the country. She asked me if I knew how to use a charkha. I said I didn't. After teaching me, she told me to spread the knowledge to others."

Following Kasturba's instructions, Ramaswamy and his wife packed their bags and moved to the Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry. There, Saraswathy taught students to spin and also took tuitions, while her husband organised meetings. Over the next five years, she taught English, Tamil and mathematics to at least 500 children.

The Salt Satyagraha and the Dandi March, 1930 Saraswathy and Ramaswamy could not stay put in Pondicherry when Gandhi urged the country to march to Dandi. They went along. "We were separated. I sat there waiting for my husband for a long time, but he didn't come. When I saw a police constable, I asked him to help me find my husband. When he refused, I shouted, 'Mahatma Gandhi ki jai' three times and walked away. He then told me that a lot of people had been arrested and that my husband could have been one of them. Indeed, he was.

Saraswathy and Ramaswamy could not stay put in Pondicherry when Gandhi urged the country to march to Dandi. They went along. "We were separated. I sat there waiting for my husband for a long time, but he didn't come. When I saw a police constable, I asked him to help me find my husband. When he refused, I shouted, 'Mahatma Gandhi ki jai' three times and walked away. He then told me that a lot of people had been arrested and that my husband could have been one of them. Indeed, he was.

After the Dandi March, the couple decided not to go back to South India. Saraswathy also remembers their involvement in the Quit India movement of 1942.

If August 15, 1947 was a day of joy for all of them, January 30, 1948 was a day she still mourns. Not only because Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated, but because she lost her husband and three sons in the riots that followed. Her husband was shot at; her children, crushed to death.

She was in Mysore to give birth to her fourth child. On hearing the news, she rushed to identify the bodies of her loved ones. Shortly thereafter, she lost her daughter to chickenpox. "I lost my family for the sake of my country. I shouldn't be crying," she says. "And yet, the tears rolled down my cheeks constantly. Those were the only times in my life when I cried aloud and accused God of being unfair to me."

She wandered around in Mumbai, Jabalpur and across Maharashtra, went to all government offices asking for a job. Everywhere she went, she was asked about certificates, but she had nothing except the one sari she wore. Those were the darkest days of her life. She was hungry, with no proper clothes and no place to stay. But she was sure about one thing -- she would not go to a Congress office and ask for money.

"My self-respect comes before everything else. I was ready to take tuitions for just Re 1."

She felt hopeful when she met a Christian teacher in Bombay. "He told me, mother, you look as if you come from a good  family. Why are you roaming around like this?' I told him, with tears in my eyes, that I wanted a job. I want to teach children and live a respectable life. Taking pity on her, the teacher arranged for her journey to Madurai where he worked, and from there to Pattukottai in Tamil Nadu.

family. Why are you roaming around like this?' I told him, with tears in my eyes, that I wanted a job. I want to teach children and live a respectable life. Taking pity on her, the teacher arranged for her journey to Madurai where he worked, and from there to Pattukottai in Tamil Nadu.

From 1949 to 2004, she made Pattukottai her home, teaching children until she reached the age of 104. She was sure about one thing though: she would never go to the government for pension or any such concessions. That was like begging for her.

Every year, on August 15, she would hoist the national flag and distribute sweets.

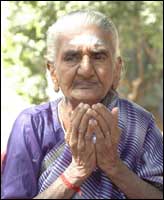

When her health deteriorated, and there was nobody to take care of her, the people of Pattukottai brought her to Vishranthi. "I resisted coming here because Pattukottai was my home since 1950! After coming here a year and a half ago, I was sad because I had nothing to do. But then, Madam (Savithri Vaithi who runs Vishranthi) told me to be happy. Now, I am."

It was only after coming here that her contribution towards making India independent was made known to the outside world.

"I love talking to people like you about what we went through. I spoke on television and on the radio. The only problem I face now is I can't sing loudly."

Saraswathy's day is never complete without her going through various newspapers. "I can't live without knowing what's happening in my country. I can only read about it now. The days of being part of the happenings are over for me."

But what she reads these days doesn't make her happy at all. What shocked her most was politicians distributing money for votes. "The first time somebody from the Congress came to me with money, I shouted at him and asked if he knew who he was offering the money to. He lost the elections!" she chuckles.

"I don't like this corrupt India. This is not the India we dreamt of, the India we sacrificed our lives for. It pains me to see corruption everywhere. But I must say there are so many loving, selfless and affectionate people in our country! It is only politicians who are selfish.'